Needs Analysis

We began our Needs Analysis phase using the Morrison, Ross, & Kemp (2006) approach. We also included the Dirksen Gap Analysis method (2016) to help identify and then fill in the gaps. This helped us establish that there was an, in fact, a demonstrated need for instruction.

This section was informed by the works of Dirksen (2016) and Morrison, Ross, & Kemp (2006).

[Regardless of] the needs analysis approach...they each share a common outcome: to provide useful data that can be used by an instructional designer to create the best possible solution.

Brown & Green, 2015, p. 53

Our Approach

Incorporating Design Thinking into our Instructional Design Process

We chose to use this approach for our Needs Analysis since it fit with our initial Design Thinking stage of Empathizing. Although we each had our own ideas and hypotheses about the problem, we were encouraged by our SME to "let the data tell the story." So we sought to understand first before defining anything.

Morrison, Ross, & Kemp Needs Assessment method (2006)

In this manner, we applied the 4-stage Morrison, Ross, & Kemp needs assessment model (2006) because it also emphasized research and data collection before defining the problem and/or need. The following 4 stages included:

Phase 1: Planning

Who is our audience, what kinds of data did we need to collect, and how would we collect it? This phase was primarily informed by our discussion with our SME as well as some desk research. We surmised that those in Generation Z and Millennials would be the primary demographic interested in a solution and that surveys and interviews would be the best way to understand the problem as they experienced it.

Phase 2: Collecting

We needed to know specific demographic information about our learners but also their deeper motivations and challenges. We created a set of questions that we divided between our survey and interview (more on this in our Learner Analysis). We distributed these surveys along our personal channels, with an option for respondents to follow-up with interviews. We collected a total of 17 survey responses and 3 follow-up interviews.

Survey Responses

17

Interviews

3

Phase 3: Analyzing

Our data helped paint a clearer picture of the need, but it was only after we applied Julie Dirksen's approach to identifying the gap (which we explain more below) that we were able to isolate where the gaps were specifically and what we needed to focus on in terms of our instructional intervention.

Phase 4: Compiling

We organized our findings from this analysis into a summary of the previous 3 stages as well as our recommendation that there was indeed a need for instructional intervention. How this intervention would look, however, would be dependent on our Learner Analysis, which was being conducted concurrently.

Gap Analysis

Where are the gaps?

Using the Dirksen approach (2016), we identified the following 3 gaps:

Knowledge Gap

Was there a knowledge gap here? 72% of our respondents had said there was, so we decided to follow up with a more objective way to measure this.

We conducted a brief 3-question quiz with our interviewees to assess their knowledge level and discovered that, on average, they were unable to answer some of the most basic questions regarding financial literacy.

Skills Gap

Could our learner perform without needing any practice?

Even if one knows the basic rules of investing, would they be confident enough to apply it in real life? Probably not without at least a little bit of practice. This indicated the presence of a skills gap as well.

Motivation Gap

When we asked our interviewees why they haven't been able to achieve the literacy they wanted, we discovered that a lot of it boiled down to reasons related to motivation.

Some lost motivation because they didn't know how or where to start; others felt that existing resources were too didactic, boring, or untrustworthy. This pointed to a real motivation gap.

Why do these gaps exist?

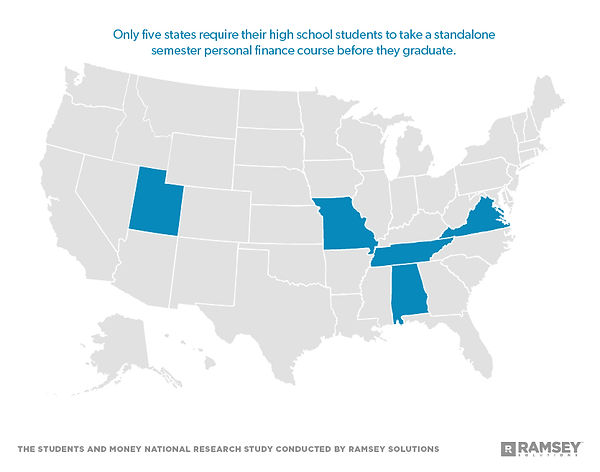

From research of the problem, we believe that the primary reason for this gap is due to the failure of our educational institutions. Financial literacy has become much more complex and multifaceted than 50 years ago, and yet, it is only required to be taught as part of the core curriculum in 5 of the 50 states!

From the survey, only one respondent mentioned she learned some basic financial knowledge at high school, but it was only covered as part of her history curriculum and the topic soon turned to poverty issues. This also proves that school instruction is not helpful.

Pain Points

So what about existing solutions? We asked our users about their experiences with what they've been using so far and summarized our findings below:

Convenience

They want to learn, but don't have the time or patience for a course. It needed to be a stress-free and convenient method.

Visual

Long texts or articles are informative but not very engaging. Our users overwhelmingly preferred a visual medium.

Credibility

Although there were plenty of free resources, the problem was whether they were created by trustworthy experts.